Introduction to nō

What is nō

Nō is a traditional Japanese performing art combining chant, music, dance, acting, as well as masks and costumes. Nōgaku comprises of two stage arts: nō, based on chant and dance, and kyōgen, its comedic counterpart, based on dialogue. Nō has been transmitted uninterruptedly for over six centuries. Playwright and performer Zeami Motokiyo (1363-1443) perfected the art of nō creating a unique blend of dramatic action, dance, and poetry. Since then, nō has been patronized by the aristocracy and, more recently, by the general public. Today, nō is considered as one of the most important forms of traditional Japanese culture. Nō may appear simple, but each of its elements has been refined over the centuries to reach today’s form.

Play types

The current repertoire consists of about 240 plays performed in various styles. These are based on myths and classical literature, and feature characters such as benevolent deities, vengeful ghosts, or valiant samurai. While many plays feature supernatural characters, there are also plays in which alive human beings are the protagonists. A few plays are based on Chinese legends; hence they are set in China. In nō plays, past and present, fantasy and reality merge to create a unique dimension shared by spirits and humans alike.

Roles

All aspects of performance are established by tradition. Actors and musicians belong to different stylistic schools and specialize in specific roles, such as main actor (shite), side actor (waki), comic actor (kyōgen), or in one of the instruments. Since they share the same repertory and performance conventions, it is not necessary for them to rehearse together. Nō performances are centered on the shite, who takes the roles of the protagonist. Generally, the beautiful masks and costumes seen on stage belong to shite families who for generations have passed on these important properties as well as the knowledge of chant and dance. Shite actors also serve as secondary characters (tsure), chorus chanters, and stage assistants. Waki actors create the circumstances for the shite to appear and tell a story. In most plays, the shite narrates and acts, while the waki listens and watches. The two roles complement each other. The four instrumentalists (three drummers and a flute player) are known collectively as hayashi. Each specializes in one instrument but also needs to master chant and dance in order to perform with the actors. Kyōgen actors provide the necessary comic relief, often serving important roles within the dramaturgy of a nō play. Some plays feature kokata or child actors: in addition to the roles of children, these actors may also portray the role of adult characters, such as emperors, or the warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune. The “purity” of a child’s presence and voice is considered suitable for the portrayal of such noble characters.

Performance conventions

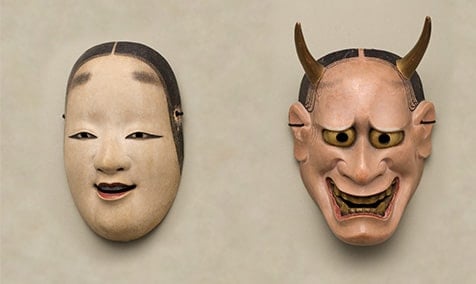

The stage reflects nō’s ritual origins, when performances were given outdoors on temporary wooden platforms. Underneath the floor are earthen pots that function as reverberating chambers when the actor stamps on the stage. Masked actors clad in lavish costumes glide over the stage like moving statues. Even slight movements may change the way a mask appears, so actors try to keep the mask at a stable angle by maintaining a low center of gravity throughout the performance. The waki is always a male character who is alive in the narrative present, hence his role does not require a mask.

The text is recited or sung by actors who function both as characters and as narrators. The chorus can take the lines of a character or can serve as the narrator. The small musical ensemble, which shares the same space with the other performers, plays set patterns established by tradition, without the aid of a conductor. The drummers’ calls between beats highlight the pauses and add drama to the music.

Movements are minutely choreographed. Each gesture is timed to the lyrics, enhancing the images evoked by the chant. An actor can express anything that is described through song or recitation, from a landscape to a feeling. At the peak of emotion, textual narration fades into pure dance and music.

Shortened versions of nō plays can be staged without costumes and masks (maibayashi) or with only one actor and a small chorus (shimai).

Nō performances are an exemplary form of “total theatre” as all its elements and performers come together on a single day to create an act of collective narration. In nō, the boundary between ritual and entertainment blurs. Since its inception, nō has been appreciated because of the beauty of texts and performance but has also been offered as a prayer for the deceased, or as an invocation for peace and prosperity.