Introduction to Kyōgen

Kyogen is a comedy that mainly describes the daily life of ordinary people in the middle ages. Unlike Noh, most of the plays are performed without masks, and a universal humanity is depicted through laughter.

- Kyōgen Humor

- Typical characters

- Special performance techniques

- Ai kyōgen

- Kyōgen masks

- Kyōgen Costumes

Kyōgen Humor

Kyōgen sees life through the lens of humor. Everyday encounters between master and servant, priest and layman, husband and wife, swindler and country bumpkin are seen to be full of bungling mistakes that lead to misunderstandings. These are overcome through witticisms, song and dance. Human failures lead to ironic twists, not catastrophe.

The humor ranges from misinterpreted instructions based on puns to willful deception to conjugal spats to ineptness, to pleasantries creating a sense celebration that are often expressed in music and dance. Still, not all kyōgen poke fun at human inadequacies. Some share the intimacy of a moonlit night, or the emotional attachment of marital love, becoming a perfect blend of humor and pathos.

Typical characters

A wide variety of characters appear in kyōgen, but at their core, they are all down-to-earth.

Tarōkaja

Tarōkaja appears in a great number of kyōgen plays as the servant of a master or manor lord. In the social hierarchy of the middle ages, the servant had a low position and could not contradict the orders of his master. In kyōgen, however, Tarōkaja defies his master at times, being armed with ready wit and stubborn arguments. Yet he can also be taken in by a swindler, or mess up plans due to his love of sake. Depending on the play, different aspects of his personality come to the fore, but what is common to all Tarōkajas is a cheerful disposition that is impossible to dislike. For this reason, he has become the most iconic kyōgen character.

Daimyō

The kyōgen daimyō are not the domain barons of the Edo period, but small, local manor lords of the middle ages. On the one hand, they strike a pose of arrogant boastfulness; on the other, they are socially inept, tearful ignoramuses. Eventually, they are embarrassed by their own mistakes. Still, playing the role of a daimyō demands a certain dignity.

Women

Many of the women appearing in kyōgen are brimming with life vigor. They express their jealousy openly and vent their anger at their husband’s trespasses. Kyōgen women are proactive and energetic.

Yamabushi and other priests

Kyōgen featuring religious prelates resound with satirical laughter. During the middle ages and early modern period, the priests were respected as intellectuals. Conversely, in kyōgen, priests forget their sutras, demand donations, and make mistakes due to their greed and lack of education.

Also, the Yamabushi ascetics, who on the strength of their austerities have superhuman powers, end up being unable to control their powers. Despite their pride in their supernatural abilities, their power is ineffectual.

Swindlers

The swindler (suppa) is one of the few bad characters in kyōgen. Actually, he is not thoroughly bad or cruel. The substance of his deceit becomes the center of the play. He twists his words artfully and deceives people. Still, his slick attitude is but another expression of human nature.

Non-human characters

Kyōgen gods are felicitous: like the seven gods of good luck who grant our desires with this-worldly rewards. These gods are not very far from humanity. Demons (oni) and thunder gods may threaten and frighten people, but they also burst out in tears and laughter, just like humans.

In addition, creatures living in proximity to civilization, like the spirits of mushrooms, mosquitoes and crabs appear. Though seemingly small and weak, they are able to overwhelm people.

Special performance techniques

Dialog lies at the core of kyōgen. Since the text is important, the actor seeks to build a voice that reaches to the farthest corners of the audience seats. The script is spoken with a distinct kyōgen-style intonation, and though the voice is adjusted to the character, there is no attempt to create a feminine voice when playing a woman. Many of the pieces highlight the telling of a story and require narrative techniques like chant and paced timing.

Movements are based on a fundamental stance and sliding walk. The body is bent forward and the hips pulled slightly back. With knees and ankles slightly bent, the actor makes sliding steps while keeping his torso steady. Realistic gestures (kata) are added to this basic stance to enact laughter, crying, praying, dipping sake, drinking, and rowing a boat. Kyōgen actions are immediately understandable to the audience, as they are exaggeratedly large renditions of realistic movements and often accompanied by onomatopoeic sounds. Being comedy, kyōgen gestures are larger than life, though the acting never descends to mere slapstick.

Song and dance often highlight a piece. In scenes featuring a sake party, for instance, short komai dances are performed, for which abstract patterns are strung together to create a dance performed to a sung text. Some plays center on singing popular ditties from the middle ages known as kouta or on chanting passages from The Tales of the Heike.

The individual actor interprets the piece and the characters, adjusting his movements and timing based on the fundamental elements of voice, stance, walk, and patterns.

Ai kyōgen

Kyōgen actors also appear as characters within nō plays, where they have the role of “ai” or “ai-kyōgen.” A great number of nō have an interlude between the exit of the shite in the first act and the entrance of the shite in the second during which the ai takes center place. Very often, the ai is a local man who appears in front of the waki, a priest, and retells the story of the shite of the first act. After recommending that the priest hold a service for the shite, he leaves. In these cases, the nō shite is often a ghost or spirit, so he narrates his tale from a past perspective of lingering regret. In contrast, the ai, being a living local man, narrates the ancient story from the perspective of present time. Then in the second act, the stage again returns to the shite’s past story. For nō that go back and forth between the past and the present, the ai is expected to adjust his narrative to the content of the nō play.

There are also nō where the ai is active throughout the play, not just between acts. The ai may play the role of a boat man, or temple worker, or a servant to a Yamabushi priest. In these nō, the ai exchanges dialogs with the shite and waki and helps move the plot forward. One might say that he has the role of producing humor and intimacy beyond the scope of the shite and waki.

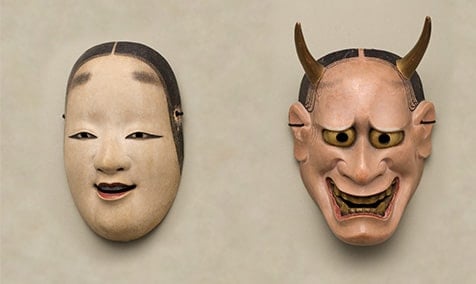

Kyōgen masks

Though for most roles, kyōgen actors perform without a mask, roles of demons, gods, animals, and spirits require masks. These kyōgen masks have an ingenuous expression. An example is the demon mask of Buaku (photo 2). The overall expression of humor derives from its features: downward slanting eyes, swollen eyelids enclosing large eyeballs, and buck teeth. The mask represents a demon who acts and thinks like a human.

Generally, women’s roles are performed without a mask. The dynamic women described above wear a “small sleeve” kimono and drape a long white cloth (binan) around their heads, allowing the ends to fall down their chests.

Still, there are times when the woman’s mask Oto is worn. The small nose and puffy cheeks lend it a sweet charm. The use of Oto is set. It is not used for roles of bossy women who turn on other characters with strings of arguments, but rather for women in plays where the man, on seeing the face of the woman, is astonished by her ugly features, and for roles of mushrooms and demon daughters. In these plays, the women do not have many lines to recite: the emphasis is on the comical effect of the mask.

National Nō Theater.

National Nō Theater.

Kyōgen Costumes

Kyōgen costumes often have playful designs. For instance, the back of the kataginu vest worn by Tarōkaja, is dyed with large impressive designs like gargoyle roof tiles, turnips, or lobsters (Photo 3). Tarōkaja’s full outfit combining a striped noshime kimono under the kataginu vest and kyōgen style hakama (pleated trousers) enhances his cheerful disposition.

Daimyō, masters, and members of the samurai class wear broad-sleeved matched suits (suō) (Photo 4) lending them dignity. Women, priests, and mountain ascetics are also defined by their costumes and hand props. Animals like foxes and monkeys are immediately recognizable from their realistic masks and bodysuits. On the other hand, costumes for horses, mushrooms, and mosquitoes are less realistic, though a resemblance is expressed through a combination of the mask, costume, headdress and hand props.

The split-toe socks (tabi) worn by kyōgen actors differ from those used by nō actors in being pale tan or yellow, and in some families striped, rather than white.

Edo Period (eighteenth century).

The Met (Mrs. Jackson Burke Gift, 1981).

The Met (Mrs. Roger G. Gerry Gift, 1997)