Nō masks

Masks are one of the most distinctive elements of nō. Some of the masks used in performance today were carved centuries ago, an exceptional feat in itself. One of the reasons why ancient masks can still be used today is that actors treat them with the utmost respect. Not only are masks precious artifacts, but also they carry with them the experience of thousands of performances in which they were used by generations of actors. Though it is possible to appreciate the refined details of masks at museums and art galleries, it is only when used in a performance that they convey their expressive potential to the fullest.

Nō masks are carved from a single block of wood. The chiseling and painting techniques create shadows and lights on the mask, making it come alive. The actors can produce expressions of joy or sorrow by slightly tilting the mask up or down, effects known as teru (to brighten) or kumoru (to cloud). Masks of fierce deities or demons, instead, express their power with sharp left-right movements. When worn, masks severely restrict the vision of the actors, who need to rely on the physical knowledge of the stage in order to perform. As the expressions on the masks respond to slight movements of the head, actors also keep a low center of gravity and walk with their feet sliding on the floor.

The standard Japanese word for “mask” is kamen (“temporary face”), but nō masks are normally referred to as omote (“face”), suggesting a quality of “truth” in the mask, an object of revelation rather than concealment. Nō masks cover the face, but not the head of the actor, leaving the chin visible, as their aesthetics do not seek stage realism.

Nō masks generally represent a character type (old man, young woman, demon, etc.), though some are used exclusively for a single role (e.g. Shōjō). Normally, masks are not used for the portrayal of male characters who are alive in the narrative present.

The models for the masks used today have their origin in the ritual items used in religious ceremonies. As nō gained popularity between the 14th and the 16th century, many new types were created. The masks used today are based on models perfected in the late 16th century. Masks have been transmitted within families of actors and Edo-period daimyō patrons as well as at temples and shrines. A large number of these are now in museums and private collections around the world.

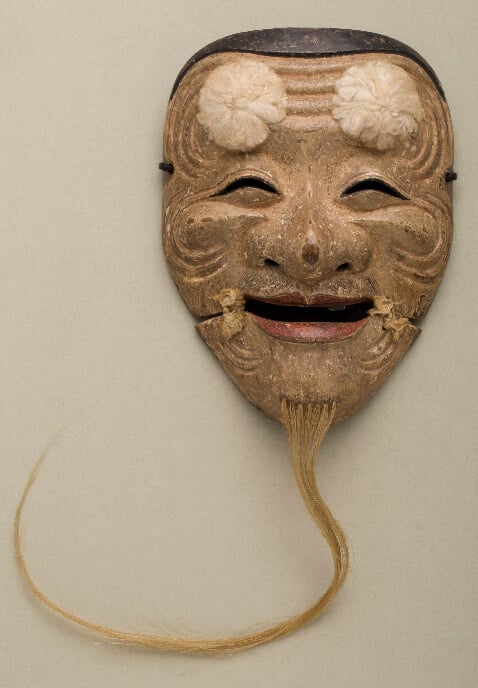

Hakushiki jō

A benevolent deity blessing the land and praying for long life. This mask is only used for the performance of Okina. Unlike other masks, the chin has been separated from the face and then attached with a cord.

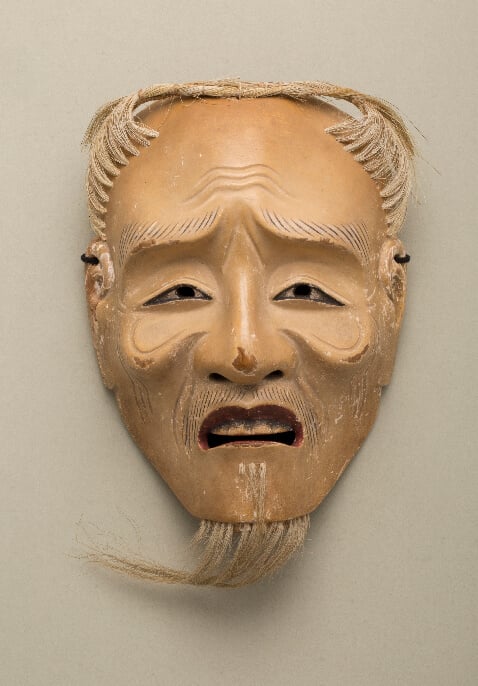

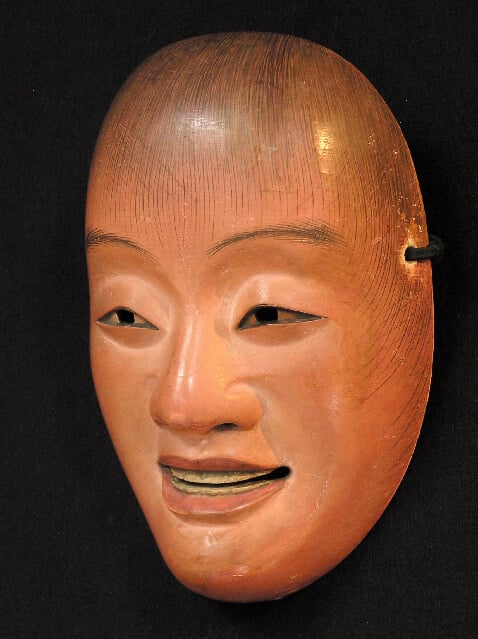

Kojō

A deity appearing in the form of a refined elderly man.

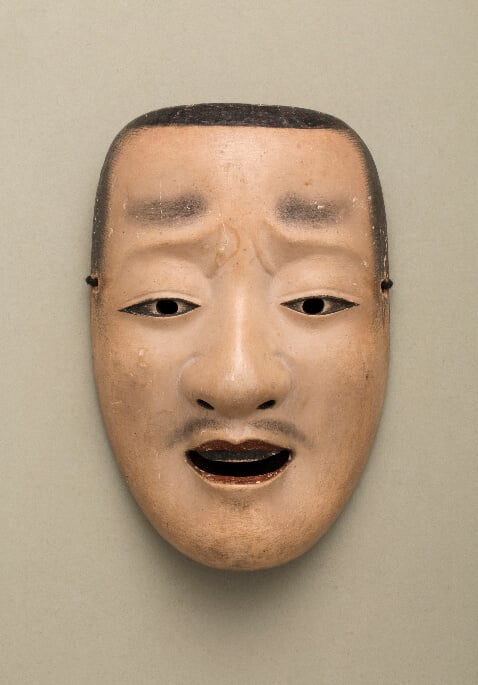

Chūjō

An aristocrat or member of the warrior elite – blackened teeth and fuzzy eyebrows indicate rank.

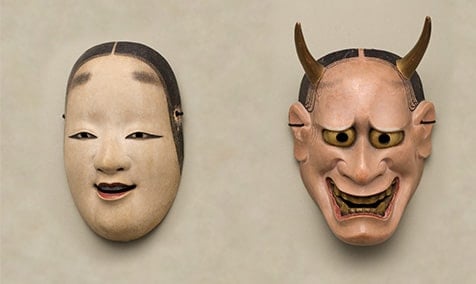

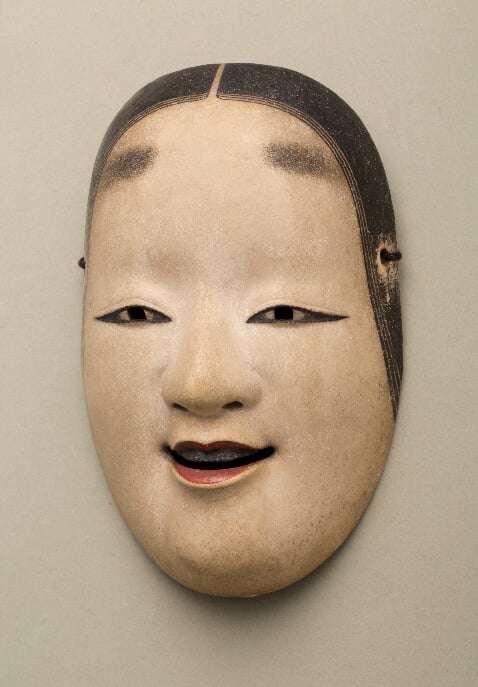

Ko-omote

A young woman – this mask can be used for a variety of characters, including female deities or spirits.

Hannya

A female demon or a woman transfigured by resentment.

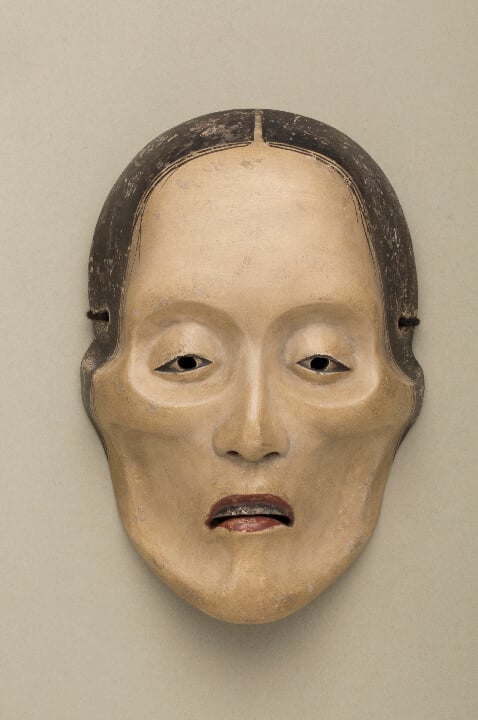

Yase onna

The ghost of a woman suffering in hell.

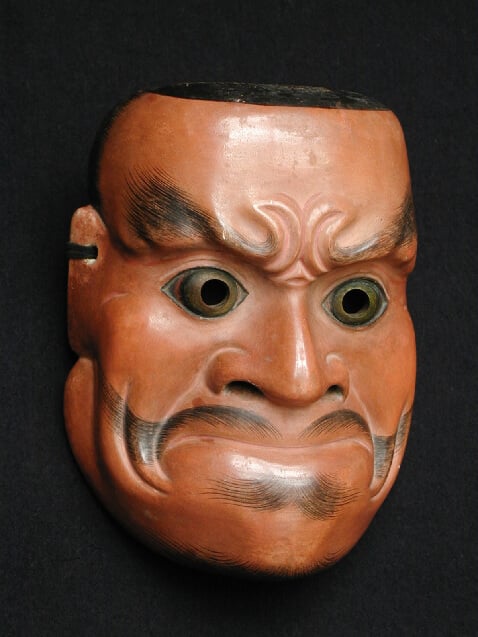

Ko beshimi

Used for roles of demons. The clamped mouth expresses power about to burst forth.

Shishiguchi

A mythical lion, companion of Bodhisattva Manjusri.

Shōjō

A sake-loving elf emerging from the water.