The Origins and Development of Nō

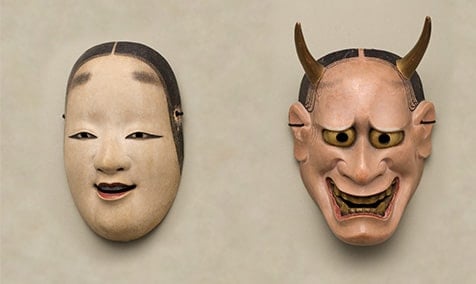

The roots of nō and kyōgen lie in sangaku performances brought from the Chinese mainland during the eighth century. Here, “san” means “non-standard” or “various”, as the sangaku pieces included a wide variety of performing arts, such as acrobatics, magic, and puppet plays. During the Heian period (894-1185) sangaku changed greatly under the influence of the city and court cultures. In addition to the original iconic arts of acrobatics and magic, comic performance that set the audience laughing gradually gathered popularity. These comedies eventually came to be called sarugaku or sarugō. Frequently performed at religious festivals such as the shūshōe and shūnie ceremonies held around New Years at large temples in Kyoto and Nara, sarugaku adapted to the new circumstances and in so doing was spurred into new developments. Specifically, the demon-chasing rituals known as tsuina or onioi, integral to these temple ceremonies, exerted a strong influence on sarugaku performance. A totally new type of masked performance was born as a dramatization of such rituals. Okina (also known as Shikisanban), a celebratory ritual using masks of smiling old men (banner photo), is thought to have started during the Kamakura period (1186-1333) and remains in the nō-kyōgen repertory today.

During the fourteenth century, this new masked drama went on to incorporate aspects of popular performances like sōka (songs) and kusemai (narrative dances). It thus developed into an innovative drama combining dialog and acting with song and dance that came to be called nō. The fourteenth century saw sarugaku troupes performing nō established in many provinces, including Yamashiro (Kyoto), Yamato (Nara), Tanba (North Kyoto) and Ōmi (Shiga). In addition, dengaku troupes, which traditionally specialized in group dances performed to drums, flutes, and rattles, gained popularity when they began to incorporate nō into their repertory. The strong competition between the players resulted in rapid developments that raised nō to a level of high artistry. Among the players were three generations of Kanze troupe masters: Kan’ami (1333-1384), who appeared as the Kanze-troupe star blossoming in the theatrical world of Kyoto, his son Zeami, who created numerous outstanding works that became the standard for nō in later generations, and his grandson On’ami (1398-1467), who gained the admiration of the Muromachi shogun and attained a firm position as an actor for the government. Due to their activities, the Kanze troupe won the competition between the various sarugaku and dengaku troupes to become the top runner in the nō world. After that, the four sarugaku troupes of Yamato, which includes the Kanze, were the driving power in the nō world up to modern times.

After its establishment, nō had its ups and downs. Over the centuries, timely patronage from powerful authorities sustained the art. The favor shown to Kan’ami and Zeami by third Ashikaga shogun, Yoshimitsu (1358-1408), is well known. Both Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598), who helped unify the nation after a period of civil war, and the fifth Tokugwa shogun, Tsunayoshi (1646-1709, r. 1680-1709), were not merely content with appreciating nō, but repeatedly performed nō on stage themselves.

Nō, however, was not always just for the powerful. Parallel to this type of gorgeous main stage activities, nō was also popularly performed in the local village festivals as jinji nō (Shrine-ritual nō). Local shrine performances began with Okina, which was amplified by chanting prayers incorporating supplications and adding lines like, “Also the desire of this shrine is xxx…. May all its wishes be granted!” When, for instance a drought lasted too long, the local community would come together and it was not uncommon for them to perform a nō that served as a rain prayer. Like this, nō was sustained for a long time as a form of ardent folk prayer. The present performance mounted as a prayer to end the novel coronavirus pandemic, relates to this aspect of nō history.